Abstract

Background/Aim: Exposure to air pollutants increased overall mortality and the risk of several chronic diseases, possibly including neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer’s disease. Recent findings suggested that chronic exposure to inhalable particulate matter could be plausibly related to neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the effect of long-term exposure to as major outdoor air pollutant, particulate matter ≤10μm (PM10), on risk of dementia onset in a cohort of subjects with mild cognitive impairment.

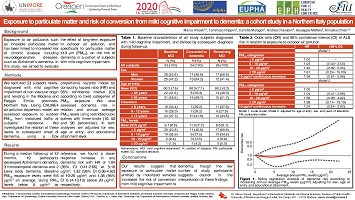

Methods: We recruited a cohort of 53 subjects newly diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment residing in Modena and Reggio Emilia provinces at the time of diagnosis. We geocoded the residence addresses of these subjects within a Geographical Information System, in which we also estimated exposure to PM10 concentration from motorized traffic at home using a validated air dispersion model. We investigated the relation of baseline exposure to subsequent conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia using a Cox proportional hazards model. We computed hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of dementia according to increasing PM10exposure, adjusting for sex, age, and educational attainment.

Results: During a median follow-up of 42 months, 24 participants developed dementia (19 Alzheimer’s dementia, 3 frontotemporal dementia and 2 Lewy body dementia). Baseline average PM10 exposure concentrations were 9.6µg/m3. Using PM10 concentrations below 5µg/m3 as reference, we found a dose-response increase in any dementia risk, with a HR of 1.04 (95% CI 0.41-2.66) 5-10µg/m3, 1.32 (95% CI 0.36-4.92) at 10-20µg/m3, and 1.38 (95% CI 0.14-13.13) above 20µg/m3.

Conclusions: Using a prospective cohort study design, we found that exposure to outdoor PM10 was associated with increased risk of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to dementia. However, the limited study size suggests caution in the interpretation of study findings.